Alternative Dispute Resolution: ADR Choices

Conversations with Claims Professionals about Mediation

By Jeff Trueman, Esq.

Having mediated thousands of cases with insurance claims professionals and having interviewed 55 of them last spring for a graduate school project, I would like to offer a summary of the challenges and concerns they typically face (as they have been explained to me) in mediation of litigated disputes. I suspect counsel may have similar challenges and concerns. Hopefully, these insights will help all participants in mediation come to the table with better strategies that produce better outcomes, or make the process more productive at least.

Mediator Qualities

Mediators need to be able to convey the limits of authority. At some point, there is no more money. Mediators who take more time with plaintiffs when a final offer is conveyed are successful more often. Some rely on past experience (“I’ve mediated with this claims professional and I can tell you this is it.”). One common problem is the distrust of plaintiff’s lawyers to believe that “this is really it.” Sometimes carriers pay more money when plaintiff’s lawyers hold out – not always but enough times to foster the impression that it will happen again.

Not surprisingly, mediators who actively assist the parties in resolving cases are preferred over mediators who are passive. Some claims professionals welcome critical, evaluative feedback from mediators when they ask the mediator for his or her opinion. It’s important to note that unsolicited evaluations are not well-received. At some point, a mediator runs the risk of being seen as the “authority figure” who thinks that he or she can predict the future. That approach can, and often does, backfire for the mediator.

Parties (and counsel) who express extreme anger are common. The mediator’s emotional intelligence and ability to manage difficult conversations can be a critical factor when choosing potential mediators. All participants need to be patient with these interactions because difficult conversations and difficult people take time. Impatience is an effective way to realize impasse.

Process

Anything can happen in negotiation and mediation. This may appear obvious. But it’s good to remember that preparation – as crucial as it is - only goes so far. One key question in any negotiation is “Who’s pulling the strings? Who’s absent and do they have authority?” Another key question is “How do I know if I’m being overconfident?” Assuming the risk of a bad outcome at trial is one thing. But assuming a calculated risk that includes an exit strategy is better because the contingency plan makes a good outcome more controllable and less dependent on chance.

Most defense counsel and claims professionals want to avoid opening presentations. I suggest you make that clear to your mediator ahead of time. On the other hand, there are sound strategic reasons to have a joint session, assuming you have a mediator who can manage it. Some claims professionals like joint sessions because it allows them to see the other side or have other parties hear from defense counsel.

Challenges with Opposing Counsel

Of course, everyone must cooperate in order to make a deal, but sometimes that just won’t happen. The hard truth is that some super-aggressive attorneys (whether they represent plaintiffs or co-defendants) will cause defendants to spend more time and money on the case. If possible, try to understand what the plaintiff actually wants; it might be a sum certain after expenses or something that makes their life easier like adjustments to their house or a motor vehicle.

When demands go up or when settlement talks break down, consider proposing a range or a bracket that incorporates the prior demand from plaintiff but shows movement on your side. If an increase in demand happens in mediation, ask for a joint session and remind the other side that you have what they want (i.e., money, perhaps a release, information, etc.). Mediations that end prematurely leave the other side not knowing what you would offer, or how much authority is available, or whether the claims professional would reconsider her valuation.

When emotions are high, consider a generous offer to start the process. Although this approach produced mixed results with one large carrier, it can deflate anger. In the right case, consider offering a portion of money up front that you’d offer anyway (i.e. for continuing medical care or devices, transportation, etc.). In one case, plaintiff’s counsel appreciated the adjuster’s overall assessment of the case and her compassion for the plaintiff, allowing her to take what time she needed to return to mediation a year later. Consider how much time and money that saved with fewer, less contentious legal battles. We are hard-wired to reciprocate. If cooperation starts on the defense side, you may engender cooperation in return. And if not, you can pull back until another opportunity emerges.

Challenges with Co-Defendants

Your mediator should take steps to address allocation problems before the mediation. When there is no communication with other adjuster(s) before mediation, why not initiate the conversation and inquire about their evaluation? Ask the question they want to answer, “Why should we re-evaluate?” Other questions that are often relevant include, “Why do you think your insured doesn’t have exposure?” “What will more discovery uncover?” “Is there room to move on the allocation percentage (yours or theirs)?” “Would the other carrier consider neutral case evaluation and take that number to their claims committee (or would you do the same)?” Remind them about facts that might rub jurors the wrong way. For example, a jury might not appreciate their insured’s conduct and put “a pox on both houses.” What are the lawyers not talking about? That may matter more to jurors than anything else.

Jeff Trueman is an experienced, full-time mediator and arbitrator. He helps parties resolve a variety of litigated and pre-suit disputes and interpersonal problems concerning catastrophic injuries, wrongful death, professional malpractice, employment, business dissolution, and real property. His writings have appeared in the Washington University Journal of Law and Policy and elsewhere.

Jeff Trueman is an experienced, full-time mediator and arbitrator. He helps parties resolve a variety of litigated and pre-suit disputes and interpersonal problems concerning catastrophic injuries, wrongful death, professional malpractice, employment, business dissolution, and real property. His writings have appeared in the Washington University Journal of Law and Policy and elsewhere.

Interested in joining the Alternative Dispute Resolution Committee? Click here for more information.

Print this section

Print the newsletter

Young Lawyers: Raising the Bar

Key Deposition Points When Deposing a Personal Injury Plaintiff

By Jami L. Ishee

Many young lawyers, even those seasoned in taking depositions, find themselves beating the steering wheel as they drive away from opposing counsel’s office over the questions they failed to ask or the testimony they wish they got more clarity on. Personally, I find the unsophisticated personal injury plaintiff to be the most frequent offender. These deponents often do not answer the exact question that is asked of them, and go off on tangents unrelated to the subject of the suit. So, how do we ensure that we stay on course, get the answers to our questions, secure clarity on contested issues, and not get distracted by the irrelevant colloquy?

Bring a detailed outline:

Your older colleagues and adversaries may think it a sign of inexperience, but always bring a detailed outline. A 30+ year old lawyer in my firm taught me this important lesson, and he still does it to this day. “Always be the most prepared lawyer in the room” is what we were always taught, so I am unsure why winging a deposition without an outline became cool. Subject headings in bold can help you speed through or skip around as need. Most importantly, with a detailed outline, you can bring all of the answers you already know from written discovery to the deposition table, which allows you to press the deponent when needed, and box them into certain positions. Having the answers to the simple questions at your fingertips also allows you to streamline the testimony and make for a cleaner transcript. For example,

Q: “Mr. Broussard, I understand you have been married twice before?”

A: “Yes.”

Q: “The first marriage was to Ms. Amy Joseph Broussard, and the second marriage was to Ms. Valerie Smith Broussard?”

A: “That is correct.”

This helps to avoid unnecessary tangents and get through the information quicker. Using the answer within the question at the start of the deposition sets the tone for the attorney to do the talking and the deponent to be agreeable. If the deponent stays with this trend, they are more likely to be agreeable to your liability questions later on. An outline also allows you to re-check what your last question was so that you can confirm you actually got an answer to your question somewhere between the deponent’s distracting story about his 1987 high speed chase that crashed his car into a ditch and boasting about his most recent ex-wife who was 30 years his junior (yes, true story).

Ask, ask, and ask again:

On the key disputed points, one question is not enough. Always ask it again in a different way to box the deponent into their position. This serves two purposes: 1. The deponent cannot later claim that they misunderstood the question or attempt a play on words to get around their deposition testimony, and 2. When used to impeach a witness at trial, the jury is more likely to pick up on the importance of the admission/testimony and be swayed by same when you demonstrate that the witness not only testified to this issue once, but twice and three times over. For example, a personal injury plaintiff testifies that he has never sought treatment for back pain in his life. You already know from medical records in your possession that he treated for back pain following a vehicle accident five years prior. In this scenario, your outline will include a list of prior injuries, so now you know that you can box the deponent in for impeachment at trial by asking repetitive questions on this point:

Q: “Mr. Broussard, in the past five years have you sought any treatment, medical or otherwise, for pain in your back?”

A: “No, I have not,”

Q: “In the past ten years, have you suffered from any back pain at all?”

A: “I just told you that I did not have any back issues before this.”

Q: “So the first time that you had ever seen a doctor for back pain in your life was after this incident?”

A: “Yes, this was the first time.”

In a case of a slip and fall, if the witness testified that they did not see a spill on the ground before they slipped, get confirmation and get them to expand the time frame:

Q: “So the first time that you ever saw water on the floor was after your fall?”

A: “That’s right.”

Q: “As you entered the aisle a few minutes before your fall you did not see a water spill on the floor?”

A: “No, I didn’t see anything”

Q: When you exited the aisle just before your fall you still did not see any water on the floor?

A: “Yes.” *

*This last response is a great example of when you should follow up for clarity—yes, you did not see water on the floor, or yes, you did see water on the floor?

Set limits:

Another good practice when deposing a personal injury plaintiff is to set limits. This can always be done for each of the Plaintiff’s alleged injuries, and should be done because this is where the damages hit hard. I like to ask the following question for each injury:

Before the fall, had you ever been to a doctor, hospital, chiropractor or any other type of health care provider with complaints of pain or problems with [INJURY/BODY PART]?

If the answer is yes, then I follow up with some questions on last date of treatment and pain level to set the limits of the alleged aggravation to each pre-existing injury:

Were you still having problems with [body part] right before the fall? (usually “no”)

When was the last time you treated for [body part] before the fall? (usually “years ago”)

On a scale of 1-10, what was your pain level before the fall?

On a scale of 1-10, what was your pain level after the fall?

On a scale of 1-10, what is your pain level as we sit here today?

For all other injuries that Plaintiff testifies were never a problem until after the incident in question, I confirm:

“So the first time you have ever been treated for [body part] was after this incident?”

This information will ultimately be revealed in the medial records, but the testimony setting the limits on these injuries is what can be compared to the medical records and used to show a lack of credibility where possible.

Be flexible:

Often times, depositions take a course of their own and may cause you to skip around to different topic areas out of order, or lead you to an area of inquiry that you did not anticipate. Always expect the unexpected and be prepared to be flexible. Take notes and indicate the testimony that you want to follow up on. I use a large asterisk. Always make it a habit to look over these notes before concluding a deposition. If needed, ask for a break so that you can review your notes and outline any additional questions you have.

Use your power of intimidation:

Unless they are a frequent litigator, your deponent likely has not been in a deposition setting before and may be nervous. Use this to your advantage. In the world of zoom depositions, court hearings, and conferences, young lawyers are often forgetting the power that comes along with your personal presence in the room. The witness is more likely to make eye contact with you, read your body language, feel uncomfortable with the awkward silent pause and offer up more details than they should, or back down from an unrealistic position when you give them the look.

Find your style:

Everyone takes depositions differently, and there is no right or wrong way. The most important thing to remember is to not be afraid to ask the hard questions! That is the point of the deposition, to find out the good, the bad, and the ugly. Even if the testimony is against your client’s interest—that is what you are there to find out.

Jami L. Ishee is a Partner with Davidson, Meaux, Sonnier, McElligott, Fontenot, Gideon & Edwards, LLP in Lafayette, Louisiana representing railroads against FELA claims and grade crossing accidents, and corporate and small business clients in the areas of insurance defense, premises liability, products liability, and general negligence defense. She is the Co-Chair of the Networking & Activities Subcommittee for the Young Lawyers Steering Committee and can be reached at jishee@davidsonmeaux.com.

Jami L. Ishee is a Partner with Davidson, Meaux, Sonnier, McElligott, Fontenot, Gideon & Edwards, LLP in Lafayette, Louisiana representing railroads against FELA claims and grade crossing accidents, and corporate and small business clients in the areas of insurance defense, premises liability, products liability, and general negligence defense. She is the Co-Chair of the Networking & Activities Subcommittee for the Young Lawyers Steering Committee and can be reached at jishee@davidsonmeaux.com.

Joint Enterprise and Joint Venture Claims in Medical Malpractice Actions

By Taylor McKenney

Introduction

Over the past few years, there has been an increase in plaintiffs pleading joint venture and joint enterprise causes of action. Surprisingly, that increase is correlated to pleading the cause of action in medical malpractice actions. This article takes you through the basics of the joint enterprise and joint venture doctrine, its application to the medical malpractice world, and the best way to defend against the cause of action.

A General Overview of the Joint Enterprise and Joint Venture Doctrine

In various jurisdictions, the law generally requires a plaintiff’s fault be compared against each defendant individually and does not permit aggregating fault of multiple defendants. An exception to this rule occurs when the defendants are involved in a joint venture or a joint enterprise.

The joint enterprise and joint venture doctrines have been recognized throughout the United States for decades. Depending on the jurisdiction, the doctrines are sometimes referenced interchangeably. If a state does recognize the difference between the two doctrines, the difference usually lies in a monetary component: a joint venture requires a pecuniary interest whereas a joint enterprise does not.

The Restatement (Second) of Torts sets forth the common elements of a joint enterprise: (1) an agreement, express or implied, among the members of the group; (2) a common purpose to be carried out by the group; (3) a community of pecuniary interest in that purpose, among the members; and (4) an equal right to a voice in the direction of the enterprise, which gives an equal right of control. See Restatement (Second) of Torts § 491, cmt. c. Each state follows some variation of the restatement for both a joint enterprise and joint venture cause of action.

Joint Enterprise and Joint Venture Claims in Medical Malpractice Actions

There has been an uptick in plaintiffs pleading joint enterprise and joint venture claims in medical malpractice cases. Despite this increase, there is limited case law to support the cause of action. Throughout the past few decades, plaintiffs have attempted to plead the cause of action in various scenarios:

- Against two physicians; Oxley v. Kilpatrick, 225 Ga. App. 838, 841, 486 S.E.2d 44, 47 (1997), rev'd in part sub nom. Rossi v. Oxley, 269 Ga. 82, 495 S.E.2d 39 (1998) and vacated in part, 235 Ga. App. 774, 510 S.E.2d 99 (1998) (alleging two physicians who jointly treated a mother with respect to the birthing process were engaged in a joint venture), Watts v. Jankowski, 411 N.E.2d 678, 680 (Ind. Ct. App. 1980) (alleging a family physician assisting a surgeon and surgeon were engaged in a joint venture).

- Against two medical facilities; Adams v. Johnston, 71 Wash. App. 599, 611, 860 P.2d 423, 429 (1993), amended on denial of reconsideration, 869 P.2d 416 (Wash. Ct. App. 1994) (alleging a medical center and a separate treatment facility were engaged in a joint venture).

- Against a facility and a provider; Mahan v. Bethesda Hosp., Inc., 84 Ohio App. 3d 520, 528, 617 N.E.2d 714, 720 (1992) (alleging a physician and hospital were engaged in a joint venture).

- Against a medical facility and a management company; Chesser v. LifeCare Mgmt. Servs., L.L.C., 356 S.W.3d 613, 627 (Tex. App. 2011) (alleging a hospital and hospital management company were engaged in a joint enterprise).

- Other variations of the aforementioned. St. Joseph Hosp. v. Wolff, 94 S.W.3d 513, 531 (Tex. 2002) (alleging a teaching hospital and a foundation that employed surgical resident were engaged in a joint enterprise), Adams, 71 Wash. App. At 611 (alleging a medical center and its medical director were engaged in a joint venture), Dang v. St. Paul Ramsey Med. Ctr., Inc., 490 N.W.2d 653, 660 (Minn. App. 1992) (alleging a government hospital and separately incorporated staff physicians’ group were engaged in a joint enterprise).

Defending Against The Claim

Although the case law to date is overall unfavorable to plaintiffs, defense counsel will still find themselves having to defend against these claims. This claim is most successfully defended on a motion for summary judgment.

Common Goal or Purpose

These claims are most difficult to defend on the element of a common goal because courts liberally construe common goals. For example, a common goal can be as broad as providing patient care. Therefore, courts are likely to find a common goal even in the absence of an express agreement. The presence of an express agreement renders it even more likely that a Court will find the presence of a common goal.

Community of Pecuniary Interest

These claims are most easily defensible on the element of a community of pecuniary interest. Given the limited case law, a motion for summary judgment should be very fact specific and emphasize the relevant provisions of the controlling agreement or testimony that indicate the absence of a financial gain between the parties alleged to be in a joint venture or enterprise. Key factors to emphasize include the absence of a right to share in profits or a duty to share in losses, limited investment of time and money into the common goal and sharing in costs without financial gain.

Right to Direct and Control

The ease in defending on the element of a right to direct and control the goal or venture is dependent on the controlling agreement. When analyzing specific provisions of the agreement in your motion, it essential to emphasize the distinctness of the two parties duties at issue. This is best emphasized by detailing the parties different obligations under the agreement and areas where one party has sole authority to make certain decisions. For example, in a matter involving a management company and a hospital, defense counsel should emphasize that the hospital provides patient care whereas the management company helps with billing and insurance.

Conclusion

Joint enterprise and joint venture claims will continue to be plead in various areas of law, including medical malpractice actions, as an attempt to aggregate fault of defendants. Although the claims are rarely successful, it is difficult to dispose of them prior to summary judgment. Regardless, these claims are defensible in a motion for summary judgment by emphasizing key provisions in the controlling agreement that show the limited financial gain between the parties and unequal control.

Taylor McKenney practices primarily in the areas of business litigation, complex torts, and professional liability. Taylor has experience in appellate practice, business litigation, construction law, insurance disputes, and marital dissolutions. Prior to Larson King, Taylor worked at a full-service, general practice law firm, where she assisted clients in all stages of litigation and handled evidentiary and motion hearings. Taylor also clerked for the Honorable Referee Mike Furnstahl of the Fourth Judicial District.

Taylor McKenney practices primarily in the areas of business litigation, complex torts, and professional liability. Taylor has experience in appellate practice, business litigation, construction law, insurance disputes, and marital dissolutions. Prior to Larson King, Taylor worked at a full-service, general practice law firm, where she assisted clients in all stages of litigation and handled evidentiary and motion hearings. Taylor also clerked for the Honorable Referee Mike Furnstahl of the Fourth Judicial District.

NHTSA Begins Regulation of ADS Technology: An Overview of Amendments to Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards

By Drew Branigan and Brandon Pellegrino

On March 30, 2022, the National Highway Traffic Safety Agency (NHTSA) published a Final Rule amending certain Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) for vehicles with automated driving systems (“Final Rule”). 87 Fed Reg 18560 (Mar. 30, 2022). These amendments will introduce new definitions and subtle textual changes to address concerns that existing language posed barriers to the development of autonomous driving technology, and to maintain a consistent level of safety for occupants of autonomous vehicles without manual controls. While the amendments in NHTSA’s Final Rule are narrow in scope, they are NHTSA’s first steps towards comprehensive regulation of fully-autonomous vehicles, and – as discussed herein – will likely be followed by additional regulation in the near future. This article will discuss the Final Rule’s most significant impacts on existing FMVSS.

Background and Recent ADS-Related NHTSA Activity

Created in 1970 by the National Highway Safety Act, NHTSA is an agency within the Department of Transportation that is tasked with reducing crashes and their resulting deaths and injuries. NHTSA achieves this through carrying out research and establishing minimum performance standards for motor vehicles aimed at protecting the public against (1) an unreasonable risk of crashes; or (2) injury or death in the event a crash occurs. These Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) are developed based on concerns and suggestions expressed by industry leaders and in-house research. The amendments announced in NHTSA’s Final Rule will be limited to the 200-series FMVSS (201-226). The only exception to this are the introduction of new terms and changes to definitions, which can be found in 571.3. However, the impact of these new terms and definitions will more or less be limited to the occupant protection standards of the 200-series FMVSS. These standards focus on occupant protection and vehicle crashworthiness in the event a crash occurs. For example, FMVSS 208 – the keystone of NHTSA’s 200-series standards – governs requirements for occupant restraint systems (airbags, seatbelts, etc.). See 49 CFR 571.208. FMVSS 201, 203, and 205 establish standards to protect occupants from impacts with the interior of a vehicle. See 49 CFR 571.201, 203, 205. FMVSS 214, 216(a), 223, 224 establish standards related to vehicle structure integrity and energy absorption from external impacts. See 49 CFR 571.214, 216(a), 223, 224. In its entirety, the 200-series FMVSS represent a 50-year collaboration between NHTSA and industry leaders to reduce injuries on the road.

As of the Final Rule’s publication, there are no fully autonomous driving vehicle operating on the roads in the United States, (NHTSA has provided exemptions to certain developers to test vehicles with high levels of autonomy in limited geographic areas), and NHTSA has not published any standard that dictates the content or performance of advanced driver assist features. In September 2016, NHTSA adopted definitions published by the Society of Engineers’ (SAE) Levels of Automation, which provides a detailed description of each level of automated driving technology- from 1 (low level driver assist) -5 (fully autonomous). See Lindsay Brooke, U.S. DoT Chooses SAE J3016 for Vehicle-Autonomy Policy Guidance, Society of Automotive Engineers International, Sept 20, 2016. A visual chart may be found here: https://www.sae.org/binaries/content/assets/cm/content/blog/sae-j3016-visual-chart_5.3.21.pdf. Instead, NHTSA has assumed an observational and advisory role by promoting the development of competing technologies, issuing voluntary guidelines for best practices, and removing existing barriers to technological development. See United States Department of Transportation, Preparing for the Future of Transportation- Automated Vehicles 3.0 (Oct. 4, 2018). NHTSA has also begun collecting information on the performance of low-level automated technology already on the road. On June 29, 2021, NHTSA issued a Standing General Order, requiring manufacturers to report crashes involving vehicles in which Level 2 technology was active. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, First Amended Standing General Order 2021-01. However, NHTSA has been hesitant to place unnecessary restrictions on this burgeoning industry, preferring instead to promote the development of competing technology in controlled environments to yield the highest quality product.

On March 30, 2020, NHTSA announced a Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) to promulgate the first ADS-focused amendments to its FMVSS. In its NPRM, NHTSA proposed limited textual changes to certain 200-series FMVSS to account for unconventional vehicle designs that are expected to be present in future ADS-equipped vehicles. Autonomous driving systems, or ADS is defined by NHTSA as “hardware or software that are collectively capable of performing the entire [dynamic driving task] on a sustained basis.” 87 Fed. Re. 18650 (Mar. 30, 2022). This definition is adopted from Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) Standard J3016_201806- Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. Id. The narrow scope of the NPRM was to respond to concerns expressed by ADS developers that outdated and ambiguous language of existing standards potentially precluded the introduction of innovative designs on the road. Namely, NHTSA was interested in the development of passenger vehicles that lack manually-operated controls. After two years of receiving and considering comments, NHTSA published its Final Rule on March 30, 2022. Consistent with its NPRM, the guiding principles of the Final Rule are to:

- Maintain the level of crashworthiness and occupant safety currently provided to occupants by applying existing test performance requirements to vehicles without manual controls

- Amend standards to account for new designs; and

- Amend requirements in a manner that minimized textual changes. Id at 18652.

Summary of Significant Textual Changes

The Final Rule begins with the introduction of new terms and modification existing definitions in Section 571.3 to clarify whether and how existing standards will apply to new vehicle designs. To account for vehicles that may be operated completely autonomously, NHTSA added the term “Manually-operated driving controls,” which is defined as:

A system of controls (1) that are used by an occupant for real-time, sustained, manual manipulation of the motor vehicle’s heading (steering) and/or speed (accelerator and break); and (2) that are positioned such that they can be used by an occupant, regardless of whether the occupant is actively using the system to manipulate the vehicle’s motion. 87 Fed Reg 18560, 18567 (Mar. 30, 2022).

The addition of this term is accompanied by the modification of the terms “Driver’s Designated Seating Position” (driver’s seat), which is now defined as the seating position “providing immediate access to manually operated driving controls,” and “Passenger Seating Position” (passenger seat) which is defined as “any designated seating position other than the driver’s designated seating position[.]” 87 Fed Reg 18560, 18566-67 (Mar. 30, 2022).

The interplay of these terms sets up the most significant change brought by the Final Rule: the modification of spatial references in test procedures and safety standards that rely on the presence of a driver’s seat or manually-operated controls. Many commenters discussed the implication of the rule for stowable or removable manually-operated controls (“Dual Capability”). In response, NHTSA clarified that vehicles with Dual Capability will be required to certify compliance with all applicable FMVSS in both modes. Vehicles with remotely accessible controls only will be considered to have no manually-operated controls. An example of this change is its impact on FMVSS 203- Impact Protection for the Driver from Steering Control System and 204- Steering Wheel control Rearward Displacement. Under the Final Rule, these standards will not apply to vehicles without manually operated controls. In vehicles with stowable controls (“Dual Mode”), the vehicle would only need to comply when the controls are deployed. Specifically, standards currently applicable to the right front outboard seating position (front right passenger seat) will now also be applied to the left-front outboard seating position (traditional driver’s seating position) in ADS vehicles without manually-operated controls. “Inboard” and “Outboard” seating positions are the preferred terms used by NHTSA to discuss reference points in the Final Rule. While their definitions are relatively technical, it is sufficient for this article to understand that outboard seating positions are located within 12 inches of the side window, whereas inboard positions are positioned greater than 12 inches away. The use of these terms assist in an accurate discussion of Final Rule, which targets vehicle designs with novel seating arrangements. Some exceptions to this general rule exist – the most significant of which is that NHTSA’s amendment to restraint requirements under FMVSS 208 will vary depending on the seating configuration in the front row. This will be discussed in greater detail below.

NHTSA’s reasoning behind this change is to provide an adequate level of safety to occupants of the left front outboard seating position when this position does not offer manually-operated driving controls. For example, as noted above, it is illogical to maintain the requirements of FMVSS 203 and 204 (related to protections provided to seating positions with immediate access to the steering wheel) in a vehicle does not have a steering wheel. NHTSA added that copious amounts of data indicate there are no technical reasons why the protections provided by a seat in the right front outboard seating position could not be mirrored by a passenger seat on the left side. Therefore, this simply provides a common-sense change to ensure that the appropriate standards are applied to new technology where application of pre-amendment standards did not make sense and potentially prevented development of certain designs. Below is a discussion of the most significant impacts of this change.

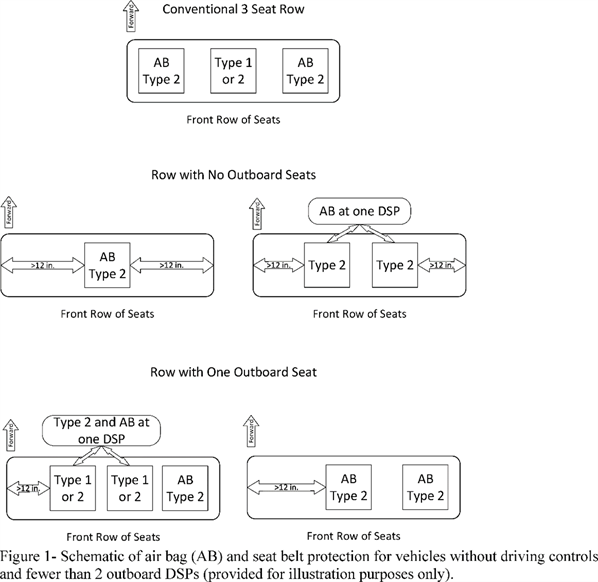

Changes Specific to FMVSS 208

FMVSS 208 – which governs vehicle restraint systems – received the greatest attention in NHTSA’s Final Rule. As mentioned above, the Final Rule will amend 208 so that the standards applicable outboard seat will generally apply to the left front outboard seat in vehicles without manually-operated controls. The most significant impact on FMVSS 208 will be the Standard’s restraint requirements for seats in the front row. Because the amended requirements vary depending on the seating configuration, NHTSA published the diagram depicted below to assist the reader’s understanding. For the reader’s context, prior to this amendment, FMVSS 208 required outboard seats to be equipped with Type 2 belts (shoulder and lap) and advanced airbags and required that inboard seats only be equipped Type 1 belts (lap belt only). See 49 CFR 571.208., “Advanced Airbag” requirements refer to occupant protections that account for real life crash scenarios in which deployment presents a risk of injury. Most importantly, advanced airbags protect occupants that may be out of position (i.e., occupants who move around during a crash because they are unbelted). Advanced airbag requirements also focus on protection small children. For example, pre-amendment FMVSS 208 required (and still requires) that the right front outboard airbag be suppressed when young children occupy the seat, or the seat is unoccupied, and required that inboard seats only be equipped Type 1 belts (lap belt only).

The Final Rule also amends the airbag suppression telltale requirements for seats in the front row. These relate to the suppression of airbags when they are either unnecessary, or pose an unreasonable risk to the occupant’s safety. In the latter case, NHTSA is most concerned with small children and out of position occupants. The telltale or warning informs the occupant of the seat whether the airbag specific to that occupant is active. The Final Rule clarifies that each designated seating position with a deployable airbag must have an individual telltale that is visible to that seat’s occupant. 87 Fed Reg 18560, 18576 (Mar. 30, 2022).19

The NPRM also considered requiring the suppression of vehicle motion when the driver’s designated seating position is occupied by a small child and ADS is engaged. In support of this, NHTSA reiterated its concern that small children should never occupy this position, regardless of the level of automation engaged. However, NHTSA removed this requirement from the Final Rule in response to comments expressing concern for unintended consequences, including suppression when the seat is occupied by adults similar in size to a small child. However, as will be discussed below, NHTSA indicated that it will be exploring alternatives to its proposed amendment.

NHTSA Action in Near Future

NHTSA has acknowledged that the changes made by this Final Rule are narrow in scope, despite receiving comments which raised additional issues related to new ADS-technology. In response to these comments, NHTSA shed light about actions it intends to take related to ADS-vehicles in the near future. For example, NHTSA’s Final Rule clarified that the 200-series FMVSS will not apply to occupant-less vehicles. However, many commenters expressed concerns over crash compatibility of occupant-less vehicles with other vehicle designs. One issue addressed throughout FMVSS’ 200-Series is Crash Compatibility, which concerns the interaction between vehicles of different sizes and density in multi-vehicle crashes. A significant portion of NHTSA’s research on this issue relates overriding and under-riding (the tendency of the front end of a vehicle to move over or under another vehicle during impact). See National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Research Program for Vehicle Compatibility (May, 2003). NHTSA responded that it would continue to monitor on-road deployment of new vehicle designs, adding that it was especially interested in the crash compatibility of occupant-less trucks. Other commenters expressed concerns that exempting occupant-less vehicles from FMVSS 205 standards requiring window glazing would pose an unintended risk to pedestrians and cyclists. Windshield glazing is a method of layering multiple sheets of glass to improve impact energy absorption and prevent injuries caused by shattering during an impact. However, NHTSA responded that after researching the issue, it found no evidence of an unintended safety benefit provided by glazing to non-occupants. Therefore, this exemption is not likely to change in the near future.

In its analysis of the changes to FMVSS 208’s restraint requirements for vehicles without driver’s seats, NHTSA also discussed a series of issues that are subject to ongoing research. For example, NHTSA announced its intent to conduct additional research on the minimum distance required between two seats with operational airbags to account for front row seating arrangements with multiple inboard positions. NHTSA is also conducting research on occupant protection standards for non-conventional seating arrangements. This includes side-facing and campfire arrangements – both of which are likely to be incorporated in future designs of ADS vehicles without manual controls. Additionally, NHTSA will revisit its proposal to suppress vehicle motion when a small child is detected in the driver’s seat during ADS operation. One alternative discussed is to require low risk airbag deployment when the driver’s designated seating position is occupied by anyone the size of a small a child. Low Risk Deployment simply refers to a reduced deployment strength for smaller occupants or occupants in close proximity to the air bag. Finally, NHTSA announced its intent to issue an NPRM on telltales and warnings for ADS-equipped vehicles. Therefore, it is possible that additional amendments may be made within the next couple of years.

Conclusion

While the changes made by NHTSA’s Final Rule are subtle and narrow in scope, they remove barriers to the continuing development of ADS technology and pave the way for broader regulation. As NHTSA discussed in response to comments to the NPRM, it already plans to conduct research and issue new NPRM’s for additional ADS-related issues. Consequently, this Final Rule signals that NHTSA intends to become more involved in the regulation ADS-technology, and more guidance is soon to follow.

Drew Branigan is an associate in the Bloomfield Hills, Michigan office of Bowman and Brooke LLP. Drew’s practice focuses on automotive product liability and warranty matters, as well as premises liability, insurance defense, and commercial litigation. He has experience in state and federal jurisdictions across the country. Drew can be reached at drew.branigan@bowmanandbrooke.com.

Drew Branigan is an associate in the Bloomfield Hills, Michigan office of Bowman and Brooke LLP. Drew’s practice focuses on automotive product liability and warranty matters, as well as premises liability, insurance defense, and commercial litigation. He has experience in state and federal jurisdictions across the country. Drew can be reached at drew.branigan@bowmanandbrooke.com.

Brandon Pellegrino is an associate in the Bloomfield Hills, Michigan office of Bowman and Brooke LLP. Brandon has experience representing businesses in product liability, personal injury, commercial and complex construction and insurance litigation. He has also focused his practice on e-discovery issues, including extensive experience with complicated national product liability discovery. Brandon can be reached at brandon.pellegrino@bowmanandbrooke.com.

Brandon Pellegrino is an associate in the Bloomfield Hills, Michigan office of Bowman and Brooke LLP. Brandon has experience representing businesses in product liability, personal injury, commercial and complex construction and insurance litigation. He has also focused his practice on e-discovery issues, including extensive experience with complicated national product liability discovery. Brandon can be reached at brandon.pellegrino@bowmanandbrooke.com.

Interested in joining the Young Lawyers Committee? Click here for more information.

Young Lawyers: Raising the Bar (Cont.)

Charitable Networking: How Giving Back Can Move You Forward

By Elise J. Berry

If you have been to a DRI seminar recently, you may have noticed a fundraiser or charity event benefiting an organization that also helps give back to the community. Some examples from Young Lawyers Seminars include volunteering at the Boys and Girls Club, cleaning and organizing at Thistle Farms, and the upcoming Cycle Bar challenge benefiting Canine Assistants, which will take place during the DRI Young Lawyers Seminar in Atlanta, Georgia! These events are not only charitable, but they are also a great way to network and meet other professionals and potential clients while serving the greater good. And in the case of the upcoming Cycle Bar challenge, allow you to mix exercise with philanthropy and networking.

I recently attended the Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital Silent Auction in St. Petersburg, Florida, benefiting the children’s hospital. My attendance and participation in the event did more than benefit the hospital itself. It allowed me the opportunity to strengthen my relationship with clients who work with the hospital, as well as network with other professionals involved in the community. The theme of the event was Movie and TV Show Characters, which paired with the open bar, allowed for easy icebreaker questions like, “Are you __?” or in my case “Who are you supposed to be exactly?” (I was Carrie Bradshaw – obviously!).

Long story short, fundraising events are an excellent way to give back to the community while also engaging in networking that is so necessary for our growth as young lawyers. In fact, there is no need to wait for the next DRI seminar to be charitable. Get involved with your local Habitat for Humanity, Guardian ad Litem, or Big Brothers Big Sisters. Dedicate a Saturday to volunteering with your local county to help pack lunches for the homeless or clean up city parks. Sure, these may not always guarantee a chance to meet other professionals or engage a potential client, but they do allow for a boost of serotonin and self-worth that may prove beneficial later on when engaging with someone at a networking event. You may eventually find that your interest in networking is now outweighed by your interest in wanting to help others – and that is the start of something beautiful.

Elise J. Berry is an attorney with Hill Ward Henderson in Tampa, Florida, and dedicates her practice to the defense of hospitals, practice groups, and health care practitioners against claims of medical malpractice. Outside of her practice, Elise gives back to her community through her involvement with the Hillsborough County Bar Association, Guardian ad Litem, and Hillsborough Association of Women Lawyers. Elise can be reached at elise.berry@hwhlaw.com.

Elise J. Berry is an attorney with Hill Ward Henderson in Tampa, Florida, and dedicates her practice to the defense of hospitals, practice groups, and health care practitioners against claims of medical malpractice. Outside of her practice, Elise gives back to her community through her involvement with the Hillsborough County Bar Association, Guardian ad Litem, and Hillsborough Association of Women Lawyers. Elise can be reached at elise.berry@hwhlaw.com.

Three Helpful Points to Encourage Young Lawyers to Join DRI

By Chalankis R. Brown

I am tired! If you need a clue about what region of the country I am from, I will rephrase my previous statement. I am tired y’all! Practicing law during a global pandemic was not exactly a part of my ten-year plan when I graduated from law school. However, there is a new crop of attorneys that have been affected by the pandemic for most, if not all of their entire legal careers. These younger attorneys have not been able to experience DRI in the same comparatively care-free way that most of our more seasoned members have been able to experience it. As we tackle the challenge of what DRI and The Young Lawyers Committee (“YLC”) looks like after a pandemic, it is important to remember what makes these groups essential. We can and should always look forward to engaging and embracing the next wave of young civil defense lawyers while staying true to the core of what makes DRI vital.

As one of the chairpersons for the Membership Subcommittee of the YLC, I will share that our committee has a lofty new member goal this year. The pandemic, as expected, has slowed our progress somewhat the last two years, but not our resolve. It is all hands-on deck time. Here, we will focus on three common sense recruiting points that our members can utilize in their efforts to recruit new members to the YLC.

The first recruiting point, and this may be low-hanging fruit, is Networking Opportunities. Young lawyers should take every opportunity to network and expand their professional circle. The YLC and DRI as a whole provide numerous avenues to make new, meaningful contacts. Specifically, the topic and practice-specific seminars, DRI’s Annual Meeting and the YLC Seminar are events that any DRI member should encourage young lawyers in their firms to attend. The in-person events provide the opportunity to meet with various in-house counsel, gain knowledge on how to grow your practice and attend presentations led by some of the best legal minds in the profession. These in-person opportunities are invaluable to young lawyers beginning to build their own practices.

The second recruiting point is Access. Becoming a member of DRI and the YLC provides access to an array of services that are helpful regardless of the prospective young lawyer’s practice area. Younger attorneys may not have the time, resources, or courage to ask a senior partner for permission to attend an in-person seminar. However, there is much more to DRI and the YLC than the in-person events. The ability to access brief databases, webinars, and the various publication materials offer practical ways for young lawyers to benefit from DRI on a consistent, if not daily basis. This access may be an easier sell to a younger attorney that is concerned about whether he or she can attend the in-person events. And it assures younger members that they are still getting their money’s worth from becoming a member and provides a ‘foot-in-the-door’ to grow their level of participation in the future.

The third and final recruiting point is Community. DRI and the YLC give young lawyers a sense of belonging. It can be overwhelming to attend a large conference where you may not know any other attendees. DRI, and the YLC especially, take the necessary steps to connect young lawyers in hope of establishing connections that will allow young lawyers to feel welcomed and ready to contribute. It is important and soothing for young lawyers to know there is a group of people just like them in any organization. DRI and the YLC allow younger lawyers to be active players, and not just another face in the crowd.

Engaging or reengaging young lawyers has never looked or felt like it does now. Nevertheless, the core principles and benefits of DRI and the YLC are attractive in any climate. These recruiting points, and the many other positives that come with being a member of DRI and the YLC are sure-fire ways to attract young lawyers.

Chalankis R. Brown is a Partner with Ball, Ball, Matthews & Novak, P.A. in Montgomery, Alabama. Chalankis can be reached at cbrown@ball-ball.com.

Chalankis R. Brown is a Partner with Ball, Ball, Matthews & Novak, P.A. in Montgomery, Alabama. Chalankis can be reached at cbrown@ball-ball.com.

Toeing the Line: The Quagmire of Multi-Jurisdictional Practice and Unauthorized Practice of Law

By Andrew B. F. Carnabuci

Even in the Seventh Century in Athens, there were institutions we would recognize as courts of law, but lawyering as a profession for pecuniary gain was illegal. One was expected to plead one’s own case in court, a practice which Aristotle fully approved. See 2 Aristsotle, The Complete Works of Aristotle, Rhetoric, 1355a35-1355b2 (trans. & ed. J. Barnes, 1991) (c. 345 B.C.) Of course, Athenians realized the advantage of having professional advocates, prohibition on legal services for hire notwithstanding. Athenians frequently engaged the many sophists of Athens—trained rhetoricians—to represent them in court for a fee, but under the guise that they were “asking a friend” for help arguing their case, even though everyone involved knew that sophist and client were not friends and that money was changing hands. See generally Anton-Hermann Chroust, Legal Profession in Ancient Athens, 29 Notre Dame L. Rev. 339 (1954).

This situation may seem somewhat arbitrary and baroque to modern readers, but is the Athenian situation described above really any more arbitrary or gratuitously baroque than the modern American legal and ethical rules addressing the multi-jurisdictional practice of law and their attendant risk of running afoul of state unauthorized practice of law rules? This article examines several types of multi-jurisdictional practice situations that defense litigators may run into and how several states handle them. Unfortunately, from this survey, no hard-and-fast rule can be extracted.

Obviously, most defense attorneys who need to litigate outside of their barred jurisdictions can do so with a pro hac vice appearance, and this may provide a simple and elegant solution to the problem. However, consider the nuances that emerge if the situation is not litigating in another jurisdiction’s courts, but rather associated transactional work. For example, A is suing B in jurisdiction X where A is headquartered but B is not. A’s local lawyers will be admitted to jurisdiction X, and if B’s lawyers are not, they can appear pro hac. But now assume that A and B settle the matter, and B’s lawyer needs to draft the release. Jurisdiction X where A resides is where the harm occurred and the lawsuit was brought, and the law of that jurisdiction will control the interpretation of the release. So what may B’s lawyer—not admitted in jurisdiction X—do in terms of drafting and advising on the release without running afoul of jurisdiction X’s unauthorized practice of law statute? There is no longer a case in which to file a pro hac appearance, and the various state bar authorities that have examined this type of issue have arrived at unharmonious positions.

Relatively recently, in 2015, New York adopted 22 NYCRR § 523, which in part allows attorneys to perform limited out-of-jurisdiction transactional work that “arise[s] out of or are reasonably related to the lawyer’s practice in a jurisdiction in which the lawyer is admitted or authorized to practice.” 22 NYCRR § 523(d). This was widely viewed as a direct repudiation of the leading California case on this type of out-of-jurisdiction practice, Birbrower, Montalbano, Condon & Frank, P.C., 17 Cal.4th 119, cert. denied, 525 U.S. 920 (1998). In Birbrower, a New York-based law firm did substantial legal work representing a California client in its arbitration against a third party. The client accused the firm of malpractice and refused to pay its bill, so the firm sued to client to collect its fees, and the client’s defense was that the firm was entitled to no fees because most of what it did constituted the unauthorized practice of law in California, despite the fact that none of the firm’s lawyers had appeared or dealt with any California court.

Attorneys had been lobbying for New York’s § 523 since the Birbrower decision, which makes sense, as New York’s status as the financial nexus of the world gives rise to a host of arbitrations, often involving out-of-state attorneys, and no one wants to complete a high-stakes arbitration and then fail to get paid on the basis of violating the local unauthorized practice of law statute.

New York’s liberal rule, however, is not representative as the rules vary widely between jurisdictions. For example, California has somewhat pared back the Birdbrower holding by enumerating very narrow exceptions allowing out-of-state practice, but has nothing approaching New York’s broad rule encompassing all out-of-state legal services “reasonably related” to a lawyer’s home jurisdiction practice. Texas draws a different distinction entirely: instead of a “broad” rule like New York or a “narrow” rule like California, Texas drafted its unauthorized practice of law statute to require the “intent to obtain economic gain” as an essential element, which would exclude any out-of-state legal service for which no remuneration is sought or provided. Tex. Penal Code § 38.123. This is yet a third way of examining the problem—by regulating only out-of-state practice done for pecuniary gain, it controls the potentially financially exploitative aspect of out-of-state practice, while retaining an out-of-state legal talent pool for pro bono matters.

So, before attorneys draw up a release controlled by out-of-jurisdiction law at the end of litigation, they should be careful to avoid unwittingly crossing the line into unauthorized practice of law. Since what constitutes “the practice of law” is almost never defined by unauthorized practice statutes, it behooves all attorneys dealing with out-of-jurisdiction work to be very careful of the unauthorized practice statutes and ethics rules in both jurisdictions, because it is often not as simple as obtaining a pro hac vice.

It has been proposed that the ancient Athenian proscription of professional commercial advocacy arose from “naïve ideas…common among primitive people” that “one who could not or would not argue his own case in person must not have much of a case.” Chroust, supra at 345. Today, we recognize many reasons why a plaintiff or defendant might wish for someone else to plead his case, and therefore a proscription on professional lawyering no longer makes sense to us. Unless and until we arrive at a corresponding recognition that our fifty-patch quilt of unauthorized practice of law statutes and ethical rules is based in part on public policy considerations that are antiquated and chimerical, lawyers must continue to take great caution when operating in these murky and fraught waters.

Andrew B. F. Carnabuci is an attorney at Rose Kallor, LLP, based in Hartford, CT, practicing primarily in labor and employment defense. His other interests include playing nurse-wife to his aging Land Rover, trap and skeet shooting, and thinking about the various ways the liberal arts can inform the practice of law.

Andrew B. F. Carnabuci is an attorney at Rose Kallor, LLP, based in Hartford, CT, practicing primarily in labor and employment defense. His other interests include playing nurse-wife to his aging Land Rover, trap and skeet shooting, and thinking about the various ways the liberal arts can inform the practice of law.

Interested in joining the Young Lawyers Committee? Click here for more information.

Appellate Advocacy Committee: Certworthy

Welcome News! The Supreme Court Proposes to Ditch the Amicus Brief Consent Requirement

By Lawrence S. Ebner

Writing amicus curiae briefs, particularly for the benefit of the Supreme Court, is one of my favorite activities as an appellate lawyer. Supreme Court amicus briefs give industry trade associations, professional organizations such as DRI (where I am a past Amicus Committee chair), non-profit public interest law firms such as the Atlantic Legal Foundation (where I serve as Executive Vice President & General Counsel), and ad hoc groups of individuals such as legal scholars, scientists, and former government officials, a direct line of communication to the nation’s highest court on the most important legal issues confronting American jurisprudence and society.

As the author of numerous amicus briefs during my half-century legal career, I know from personal experience that when an amicus curiae is truly a “friend of the court,” the brief will provide additional—not duplicative—legal arguments, information, and/or perspective that may benefit the Justices in their decision-making. My article, "Learning the High Art of Amicus Brief Writing" (For The Defense, Feb. 2017), provides some practical tips for making amicus briefs effective. And in my view, when an attorney is relieved of the psychological burden of billing by the hour, researching and writing an amicus brief can be a truly pleasurable and creative, as well as intellectually stimulating, experience (see my article, "Flat-Fee Billing Can Liberate Attorneys," For The Defense, Feb. 2020).

Of course, there are some potential procedural pitfalls. At the certiorari petition stage, these include the 10-day advance notification requirement and the non-extendable 30-day deadline for filing petition-stage briefs. See Sup. Ct. R. 37.2(a). And at both the petition and merits stages, there is Rule 37.6, which as a practical matter, requires amicus counsel to assure the Court (in the first footnote on the first page of the brief) that the brief has not been authored or financed, in whole or part, by a party or its counsel.

What about consent? The Supreme Court’s longstanding rule has been that non-governmental amici must obtain the litigating parties’ consent, or the Court’s permission, for the filing of an amicus brief. See Sup. Ct. R. 37.2(a), 37.3(a). (Under Rule 37.4, federal, state, and local government amici do not require consent or leave.) Requesting and granting consent for non-governmental amicus briefs not only is the nearly universal practice in the Supreme Court, but also is expressly encouraged by the Rules, which state that the filing of a motion for leave to file an amicus brief “is not favored.” Id. § 37.2(b).

Surprisingly, on March 30, 2022, the Supreme Court announced proposed rules changes—including elimination of the requirement to obtain consent for the filing of an amicus brief! The Clerk’s explanatory comment accompanying the proposed revision states that “[w]hile the consent requirement may have served a useful gatekeeping function in the past, it no longer does so, and compliance with the rule imposes unnecessary burdens upon litigants and the Court.”

Comments that I prepared and submitted to the Court’s Rules Committee on behalf of the Atlantic Legal Foundation applaud this long-overdue proposal. Our comments discuss why, as a practical matter, the need to obtain consent serves no useful purpose and sometimes can impede preparation or submission of amicus briefs.

If the proposed rule change is adopted, opposing counsel who lack Supreme Court experience no longer will be able to engage in the bush-league, and always futile, practice of withholding or delaying consent for the filing of a timely, Rules-compliant amicus brief. Nor will inexperienced opposing counsel be able to try to hold an amicus brief hostage, making consent contingent on their prior review of a draft of the brief. Although experienced appellate attorneys do not engage in practices like these, only a small fraction of the hundreds of thousands of attorneys who have paid the fee to join the Supreme Court Bar are appellate litigation specialists.

This leads to a more fundamental point: Since the purpose of an amicus brief is to benefit the Court (as well as the supported party), its submission should not be dependent, even in theory, on the other side’s consent. Elimination of the consent requirement implies that the Court welcomes amicus briefs. The Court grants review in cases involving important legal issues that often transcend the immediate interests of the litigating parties. It makes sense, therefore, to afford all interested organizations and individuals a voice on such issues.

Let’s hope that the Supreme Court acts promptly to adopt the revised amicus brief rule and eliminate the consent requirement, and that federal courts of appeals and state appellate courts do the same.

Lawrence S. Ebner is vice chair of DRI’s Center for Law and Public Policy. In addition to serving as Executive Vice President & General Counsel of the Atlantic Legal Foundation, he is founder of Capital Appellate Advocacy, a boutique law firm in Washington, D.C.

Lawrence S. Ebner is vice chair of DRI’s Center for Law and Public Policy. In addition to serving as Executive Vice President & General Counsel of the Atlantic Legal Foundation, he is founder of Capital Appellate Advocacy, a boutique law firm in Washington, D.C.

Interested in joining the Appellate Advocacy Committee? Click here for more information.

Employment and Labor Law: The Job Description

Appeals Court Assesses Date When Biometric Privacy Claims Accrue

By Joseph M. Gagliardo

In Watson, et al. v Legacy Healthcare Financial Serv- ices, LLC, et al., 2021 IL App (1st Dist.) 210279 (Dec. 15, 2021), the 1st District Appel-late Court decided the issue of when a claim accrues under the Biometric Information Privacy Act (740 ILCS 14/1 et seq.).

Plaintiff Brandon Watson, who had worked at various Legacy Healthcare facilities in Chicago, alleged that from the start of his employment with the defendants in 2012 through the end of his employment in 2019, he was “required to have his fingerprint and/or handprint collected and/or captured so that defendants could store it and use it moving forward as an authentication method.” Specifically, the plaintiff alleged that he was “required to place his entire hand on a panel to be scanned in order to ‘clock in’ and ‘clock out’ of work” each day.

The act requires an entity that utilizes biometric data (1) to publicly provide a written policy governing the retention and permanent destruction of biometric information, to inform any subject in writing that his or her biometric information is being collected or stored, (3) to inform the subject in writing of the specific purpose and length of time for which his or her bio- metric information is being stored and used, and (4) to obtain his or her written con- sent. 740 ILCS 14/15(a), (b).

The complaint alleges that the defendants violated the act by failing to satisfy all four of these requirements.

In response, the defendants filed a section 2-619 motion to dismiss, arguing that the plaintiff ’s claim accrued on the first day they collected his biometric information and that the plaintiff ’s suit thus was time-barred. In the alter- native, the defendants argued that the plaintiff ’s claim was preempted by the Workers’ Compensation Act (820 ILCS 305/5(a), 11) and the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947 (LMRA) (29 U.S.C. Sec. 185(a) (2018)).

The trial court granted the defendants’ motion to dismiss, finding (1) that the plaintiff ’s claim accrued with the initial scan on Dec. 27, 2012; (2) that the statute of limitations was five years; and (3) that his suit, filed on March 15, 2019, was therefore time barred.

The trial court observed: “This holding disposes of the case, but the Court will address defendants’ other arguments for the record.” The trial court then found that the plaintiff ’s claim was not preempted by either the Workers’ Compensation Act or LMRA.

The trial court subsequently granted the plaintiff ’s motion for entry of a finding pursuant to Illinois Supreme Court Rule 304(a) that there was no just reason to delay an appeal from its orders.

The act itself does not contain an express statute of limitation or set forth an accrual date. On appeal, neither side contested the trial court’s finding that the statute of limitations is five years. As a result, the issue of the applicable term of years of the statute of limitations was not before the Appellate Court on the inter- locutory appeal.

After an extensive review of the act and the parties’ arguments, the appellate court found that the plain language of the act, its legislative history and purpose, and the dictionary definitions of its key terms compelled the court to reject the defendants’ argument that the accrual date occurred with the first collection of plaintiff ’s fingerprint or handprint. The court went on to state that the plain language of the statute establishes that it applies to each and every capture and use of the plaintiff ’s fingerprint or hand scan.

In response to the defendants’ argument that, if the accrual date is not the first collection, then damages will be ruinous for them, the court stated it did not need to decide whether each scan was a new and separate violation or a continuing violation. “All we have to determine now is whether plaintiff ’s suit against these defendants survives their motion to dismiss.”

The court further stated that questions relating to damages were not before the court, and it was not going to decide the preemption arguments raised by the defendants, as all defendants who are parties in the case before the trial court, were not par- ties to the appeal. The court further noted that it has already accepted a certified question regarding the issue of whether the LMRA preempts claims under the act, and this question has been fully briefed in another appeal. See Watson v. Legacy Healthcare Financial, et al., 2021 IL App (1st) 210279.

Joseph M. Gagliardo is a lawyer with Laner, Muchin Ltd. He has counseled and represented private and governmental employers in a broad range of employment matters for more than 30 years.

Joseph M. Gagliardo is a lawyer with Laner, Muchin Ltd. He has counseled and represented private and governmental employers in a broad range of employment matters for more than 30 years.

Interested in joining the Employment and Labor Law Committee? Click here for more information.

Insurance Law: Covered Events

Professional Liability Insurance Law SLG Leadership Notes

By William McVisk

Edited by Suzanne Whitehead

The ILC’s Professional Liability SLG offers numerous opportunities for members to participate and to learn about developments in Professional Liability coverage issues. During the past year, the PL SLG has met quarterly. At these meetings, we discuss business, but also have discussions of relevant professional liability topics. For example, three of our members gave a presentation on “Policy Limits Demands and Eroding Policy Limits,” which was well attended both by outside counsel and in-house attorneys. In addition to meetings on professional liability issues, SLG members have the opportunity to publish in DRI publications, such as The Brief Case. In this issue, two SLG members are publishing articles. If you are interested in joining our subcommittee please contact me at wmcvisk@tresslerllp.com or co-Chair Brian Bassett at bbassett@tlsslaw.com.

William McVisk is a litigation attorney, focusing on insurance coverage and bad faith litigation.He is a partner at Tressler LLP in Chicago. He is the Illinois State Representative for DRI and is chair of the DRI Insurance Law Committee’s Professional Liability SLG.

William McVisk is a litigation attorney, focusing on insurance coverage and bad faith litigation.He is a partner at Tressler LLP in Chicago. He is the Illinois State Representative for DRI and is chair of the DRI Insurance Law Committee’s Professional Liability SLG.

Advertising Injury and Personal Injury SLG: The Insurance Law Committee’s Coverage “B”-Keepers

By Daniel I. Graham, Jr.

Edited by Suzanne Whitehead

Biometrics and violations of privacy. Misuses of social media. The infringement of intellectual property. In courtrooms throughout the country, judges are assessing the types of 21st century risks and exposures to which “personal and advertising injury” liability coverage might apply. And as they do, they contribute to an ever-evolving legal landscape with outcomes that can vary from state to state and courtroom to courtroom.

The Advertising Injury and Personal Injury Subcommittee brings together practitioners throughout North America to share their experience with this developing body of case law. Our members share their insights in DRI publications. They speak on these cutting-edge topics at the Insurance Law Committee’s popular educational events, including the Insurance Coverage and Claims Institute and the Insurance Coverage and Practice Symposium. And they welcome your involvement.

So, if you feel the rush of adrenaline every time you read a decision analyzing whether a particular claim involves implied disparagement … if you lie awake at night contemplating how broadly courts construe the wrongful entry offense … then we encourage you to join the Advertising Injury and Personal Injury Subcommittee. Please do not hesitate to contact me at dgraham@nicolaidesllp.com for more information.

And if our subcommittee isn’t for you, please know that the Insurance Law Committee offers its members plenty of other subcommittees where they can learn, contribute, and participate. We invite you to join us!

Daniel I. Graham, Jr. is a founding partner with Nicolaides, Fink, Thorpe, Michaelides, Sullivan LLP. He assists his insurance company clients in evaluating the coverage issues that intellectual property infringement, privacy, and unfair business practice claims present and represents his clients’ interests in technology-related coverage disputes throughout the country. Dan, who has been recognized by Leading Lawyers Network, Chambers USA, and Super Lawyers, is an active member of DRI’s Insurance Law Committee.

Daniel I. Graham, Jr. is a founding partner with Nicolaides, Fink, Thorpe, Michaelides, Sullivan LLP. He assists his insurance company clients in evaluating the coverage issues that intellectual property infringement, privacy, and unfair business practice claims present and represents his clients’ interests in technology-related coverage disputes throughout the country. Dan, who has been recognized by Leading Lawyers Network, Chambers USA, and Super Lawyers, is an active member of DRI’s Insurance Law Committee.

Interested in joining the Insurance Law Committee? Click here for more information.

Insurance Law: Covered Events (Cont.)

SEC Climate Rules: Increasing D&O Risk May Accompany Enhanced Disclosures

By Laura A. Foggan, Miranda H. Turner, and Kevin Cacabelos

Edited by Suzanne Whitehead

On March 21, 2022, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed climate-focused disclosure requirements that, if they become effective, will make public companies’ assessment of climate risk mandatory and force an examination of their environmental impact. The proposed requirements, titled The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors, would significantly increase the information public companies must include in their filings, creating a new and heavy disclosure burden on many companies, while also potentially increasing their exposure to activist securities litigation and director and officer liability.

Informed by existing frameworks such as the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and the GHG Protocol, the proposal is intended to standardize reporting of climate-change risks, as well as enhance the comparability and reliability of information being made public. However, the effort to eliminate uncertainty in standards and measurement of company statements regarding climate-change risks, itself uncertain, may have the unintended effect of prompting new claims targeting climate-related policies and disclosures and GHG reduction efforts.

Overview

Under a proposal the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued for public comment on March 21, 2022, publicly traded companies would have to provide detailed information about climate-related financial risks and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The disclosure requirements vary depending upon a company’s status and size, but generally represent a significant expansion of public company obligations in this area.

Specifically, the proposal would require disclosure of information about how climate change could impact a business’s strategy, business model and outlook, processes for managing climate-related risks, and the impact of climate-related events on the company’s business and financial statements over the short, medium and long term. The proposal requires disclosure of direct GHG emissions (i.e., “Scope 1”), indirect GHG emissions from the purchase of electricity or other energy sources consumed by the company (i.e., “Scope 2”).

In some situations, the rule will also require disclosure of indirect GHG emissions from both upstream and downstream sources (i.e., “Scope 3”). The reach of Scope 3 disclosure is potentially very large, but proponents of Scope 3 disclosures assert that such a broad reach is important to capture a company’s true carbon impact and, although a company may not control the activities in its value chain that produce Scope 3 emissions, it nevertheless may influence those activities, for example, by working with its suppliers and downstream distributors to take steps to reduce those entities’ direct GHG emissions. Scope 3 may range from activities that relate to the initial stages of producing a good or service, such as materials sourcing, materials processing, and supplier activities (upstream), to activities that relate to delivering a finished product or providing a service to the end user, such as packaging, transportation and distribution, use of sold products, end of life treatment of sold products, and investments (downstream). See proposed 17 CFR 229.1500(t). Scope 3 disclosures are required only if the emissions are material or if the company has laid out targets for them.

The information required to disclose direct emissions and indirect GHG emissions from the purchase of electricity or other energy sources (Scope 1 and 2 disclosures) can be reasonably expected to be within the company’s control, but disclosure of indirect emissions from upstream and downstream sources (Scope 3 disclosures) would necessitate reliance on others. Because they may rely on external information sources -- such as emissions reported by parties in the company’s value chain, or data derived from economic studies, published databases, government statistics, industry associations, or other third-party sources -- Scope 3 disclosures present unique issues in data collection and measurement.

Disclosure Concerns

The SEC disclosure requirements, if adopted, will present challenges and potential for additional risk for disclosing companies. Information accuracy may be a challenge, and the disclosure rule will place a cost burden on companies, potentially forcing them to hire and rely on third-party consultants.

While many large public companies have already been measuring their climate risk, this isn’t the case for all public companies. Every public company will now need to assess the climate-related information they collect and whether additional data will be needed to meet the SEC disclosure requirements. Surveys suggest that many companies do not have adequate ESG data, in particular data from their supply chain partners.

Further, accuracy and consistency in disclosures will be very important. Under the proposed rule, registrants would need to, for example, disclose the financial impact of climate events, track and disclose climate-related expenditures, and measure, disclose, and track GHG emissions. These disclosures must be made in a consistent and defensible way. And companies will need an independent third party to attest to their GHG emission disclosures.

Another significant question is how to assess the materiality of climate-related risks to determine what information must be disclosed. The proposed rule compares the materiality determination of climate-related risks to the materiality assessment for purposes of preparing the management discussion and analysis (“MD&A”) section in a registration statement or annual report, i.e., known material events and uncertainties that are reasonably likely to cause reported financial information not to be necessarily indicative of future operating results or of future financial condition. For climate disclosures, the Commission is emphasizing an approach to materiality that considers the magnitude and probability of the risk materializing over the short, medium, and long term. The Commission also proposes that public companies disclose impacts on specific categories, including business operations, products or services, suppliers and other value chain parties, climate-risk mitigation efforts, such as adopting new technologies, and expenditures on research and development.

The effect of the rule on public companies is obvious, but the proposed rule may also have an indirect effect on non-public companies, which will likely face increased pressure to evaluate their own GHG emissions from activists and even from public companies that are their business partners, who will need their suppliers to provide data on GHG emissions.